[[{“value”:”

[[{“value”:”

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

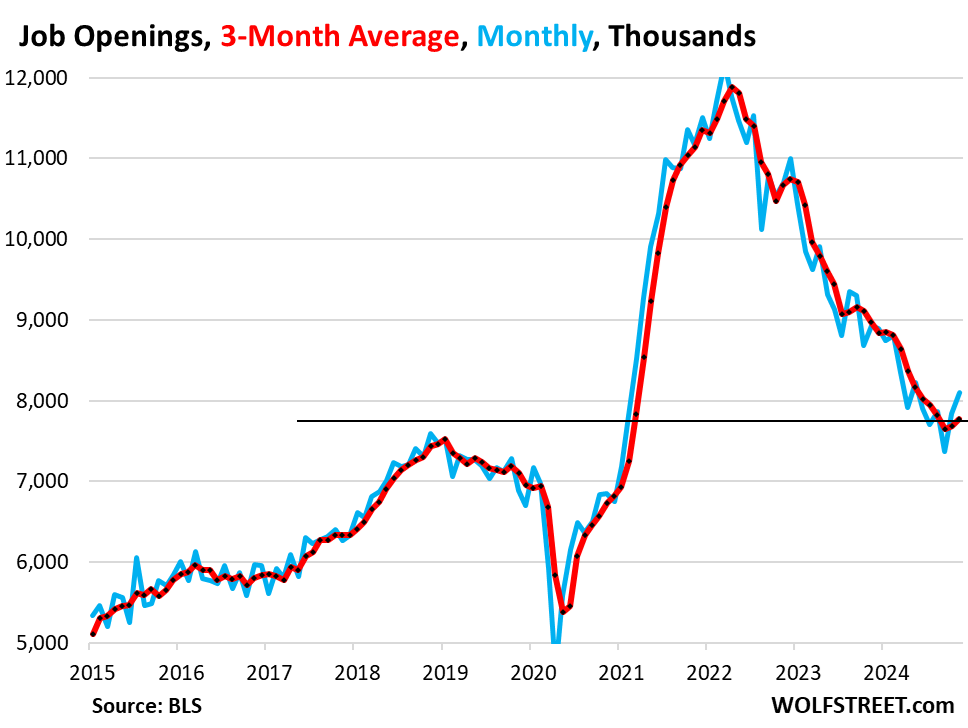

October’s majestic jump in job openings was revised even higher, and in November, job openings jumped by another 259,000, to 8.10 million (blue in the chart below), the highest since May and well above the prepandemic record in late 2018, and the three-month average (red) rose for the second month in a row, as the underlying dynamics of the labor market retightened, according to the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) from the Bureau of Labor Statistics today. This data is based on surveys of about 21,000 work locations, and not on online job listings.

Since fewer people are quitting their jobs – voluntary quits have come way down from the pandemic highs – they’re leaving fewer empty slots behind, which should reduce job openings to refill the empty slots. But instead, job openings have now jumped substantially despite fewer quits, which is interesting because it points at more new slots to be filled that didn’t exist before – and thereby, it points at a sudden U-turn in the demand for labor, and not just churn.

Big jumps occurred in the highly-paid and huge category of professional and business services (+273,000) and also in finance (+105,000).

The Fed has been backpedaling on rate-cut expectations for over two months, in light of the solid labor market conditions and re-accelerating inflation. The big salvo came at the FOMC meeting in December, when it projected only two 25-basis-point cuts this year, down from four in the prior meeting, and it has thrown doubt on those two cuts. It raised its projections for PCE inflation by the end of 2025 to be higher than now. It raised the projections for the “longer run” federal funds rate to 3.0%. And it lowered its projection for the unemployment rate by the end of 2025 to 4.3%, which would be historically low.

Today’s labor market data on job openings adds more confirmation to that scenario. And inflation data has been accelerating for months, both the CPI measures which came in hotter and were revised higher, and the PCE price index data that the Fed cites, which led Powell to say: “We still have work to do.”

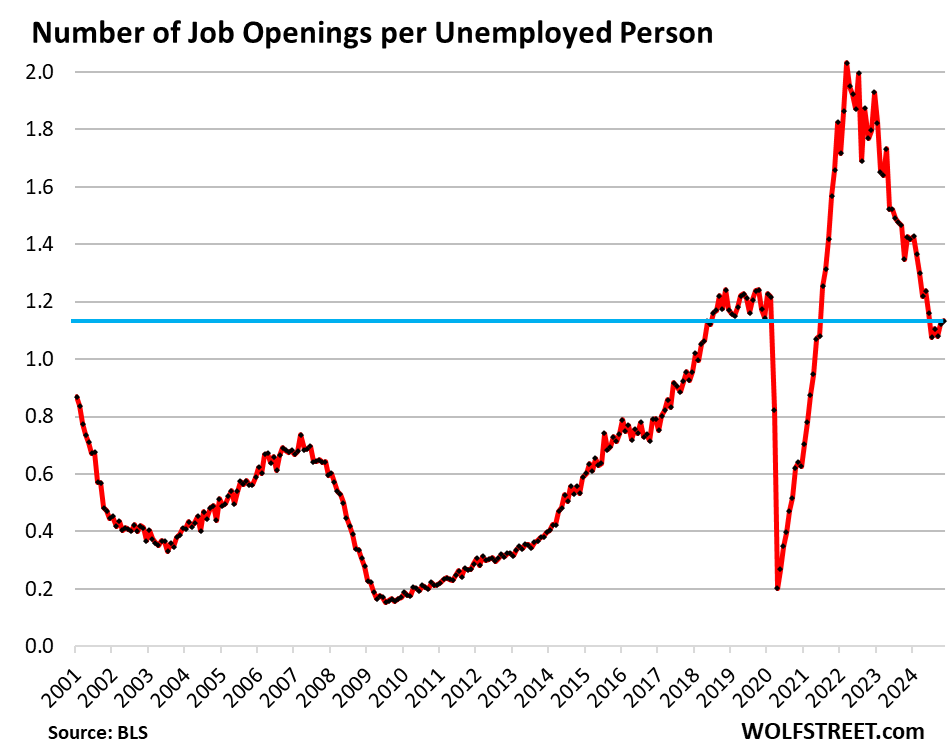

The number of job openings per unemployed person is a metric of labor-market tightness that Powell cites a lot. It ticked up to 1.13 openings per unemployed person, the highest since June. There were 8.098 million job openings in November for 7.145 million unemployed people looking for work.

The sharp decline of this ratio through the first half of 2024 was one of the reasons Powell cited specifically in support of the monster 50-basis-point cut; he’d said the metric showed that enough heat had come out of the labor market and that the Fed didn’t want it to cool further. And it stopped cooling further. And it remains relatively hot, and is warming up further:

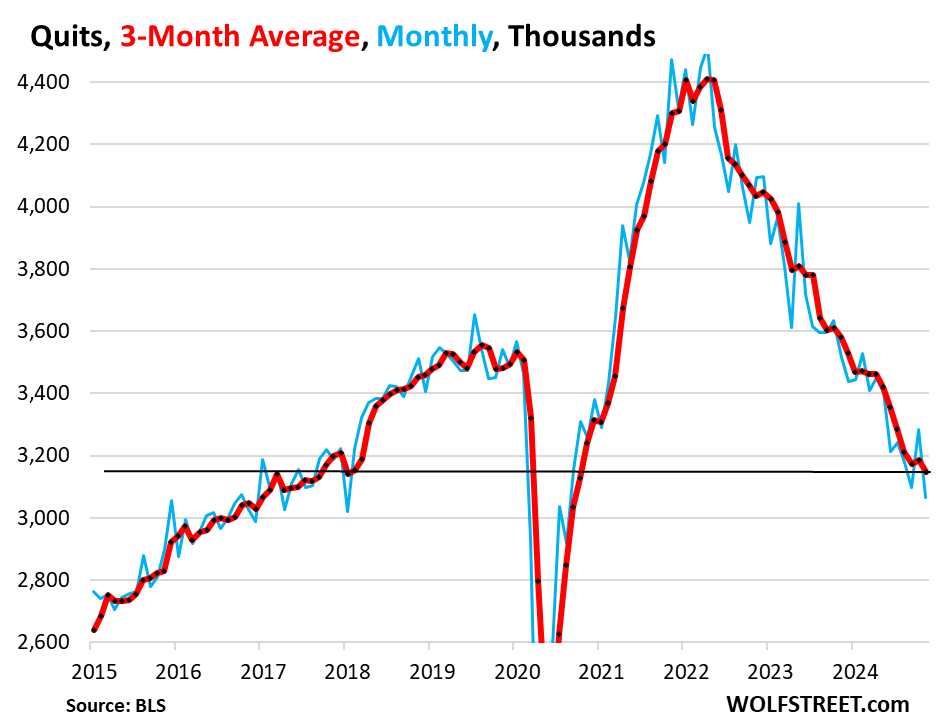

Voluntary quits fell by 218,000 in November to 3.06 million. Revisions reduced October’s jump. The three-month average dipped to 3.15 million, about where it had been in early 2018.

The massive churn in the workforce during the pandemic, when workers quit all over the place to jump jobs and industries to improve their pay and working conditions, and to better match their skills and aspirations, had triggered the biggest pay increases in decades. Maybe this massive reshuffling of jobs and skills had the effect that more people are where they like to be, and that companies are taking care of them better in order to not lose them.

Fewer voluntary quits would normally mean fewer newly open slots left behind that have to be filled, so fewer job openings, and fewer hires to fill those openings. And that’s how it played out earlier in 2024.

But over the past two month, the dynamic changed: job openings jumped despite fewer quits, suggesting that more new slots were created that need to be filled.

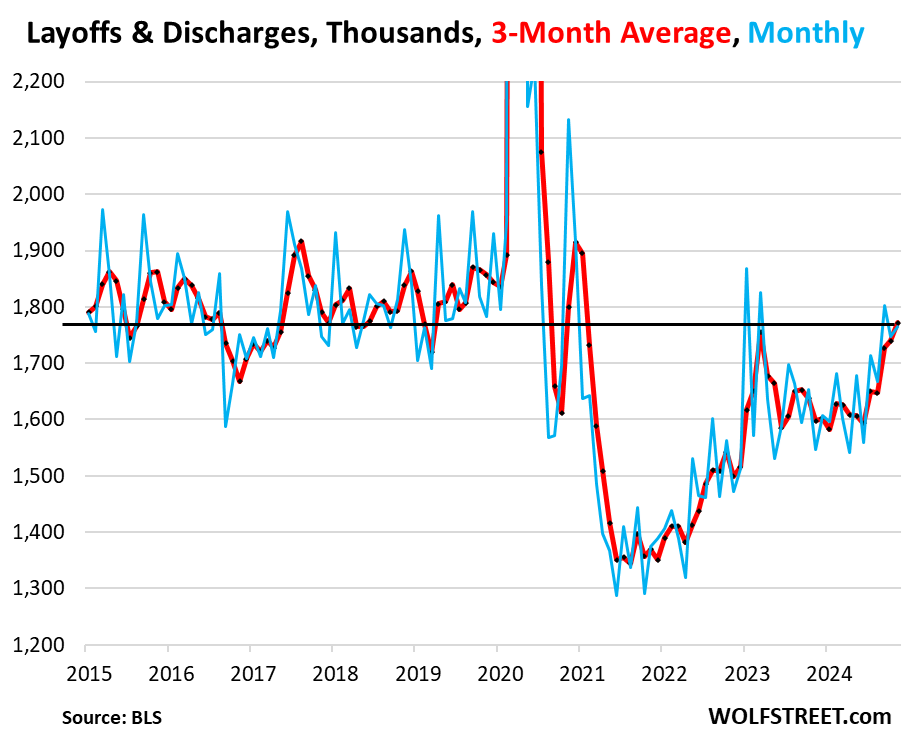

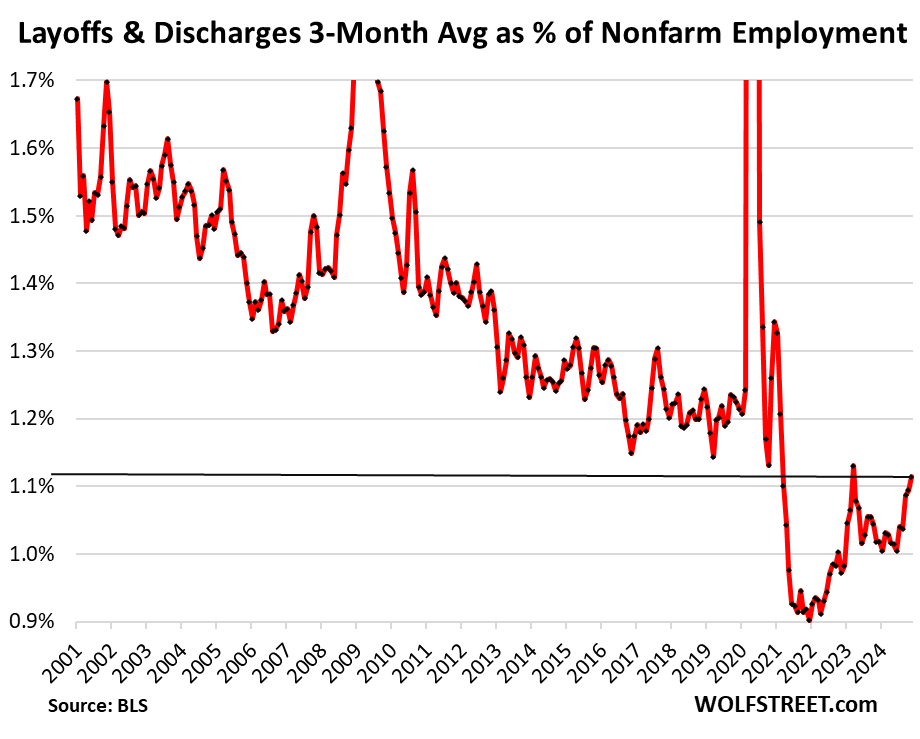

Layoffs and discharges rose by 17,000 in November to 1.76 million, after the sharp drop in the prior month. The three-month average rose to 1.77 million.

Layoffs and involuntary discharges include people getting fired with or without cause, but do not include retirements, deaths, etc., which are in a separate category (“other discharges”). Getting fired is a standard feature in the American workplace even during the best times.

Layoffs and discharges as percentage of nonfarm payrolls, which accounts for growing employment over the years, rose to 1.11%. The three-month average rose to 1.10%. Both are far below any time during the pre-pandemic years in the JOLTS data going back to 2001.

In other words, compared to the size of nonfarm employment, layoffs and discharges are historically low. It documents that employers are hanging on to their workers.

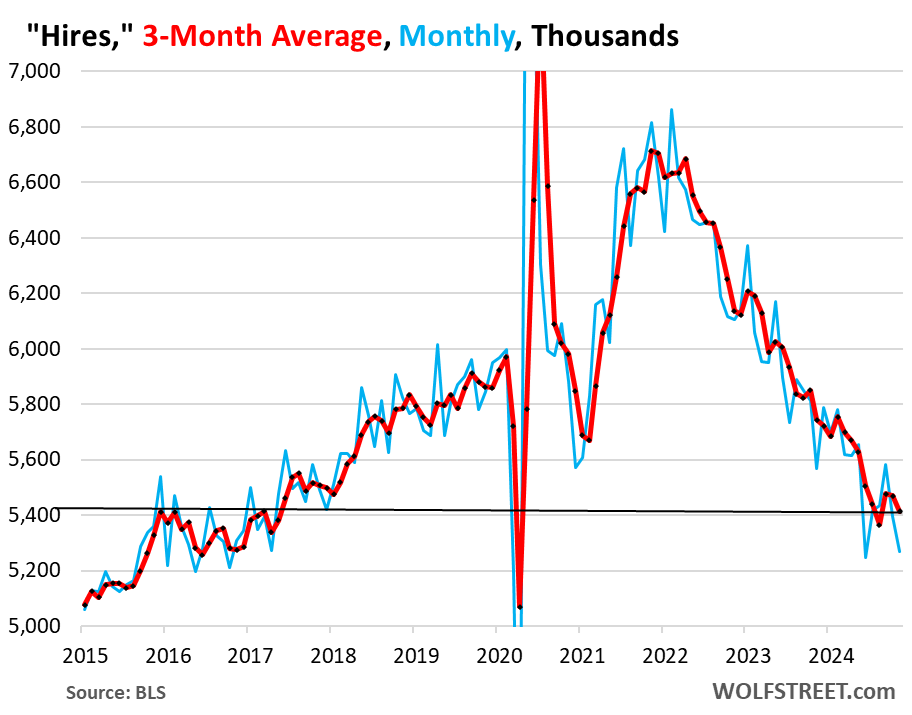

Hires to replace workers who quit or were laid off or discharged, and to fill new roles fell by 125,000 in November, to 5.27 million, the second month of declines, following three months of increases. The three-month average declined to 5.42 million hires.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

The post Labor Market Dynamics Retighten, Job Openings Jump Again. Fed Faces Scenario of Solid Job Market, Re-accelerating Inflation appeared first on Energy News Beat.

“}]]