[[{“value”:”

[[{“value”:”

Hiring Begins to Shift to Private-Sector where Hiring Jumped, while Hiring by Governments Slumped.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

The circular relationship between quits, job openings, hires, and fires – the data released today – shows the churn in the labor market, in addition to growth aspects. And now it also begins to show a shift from government hiring to private-sector hiring.

Labor-market churn went wild in 2021 and 2022, when workers quit in huge numbers to jump to better jobs, thereby leaving behind large numbers of slots that had to be filled, and then a large number of hires to fill those left-behind job openings. This churn reshuffled the entire labor market, and many workers ended up with jobs that paid more and matched their skills better than before.

But starting in mid-2022, Corporate America, especially Big Tech, cracked down on churn and soaring wages with huge layoff announcements to scare the bejesus out of their employees and make them thankful they even still had a job. And worried workers quit quitting. So left-behind slots plunged, and job openings plunged, and hires to fill those job openings also plunged.

And the low-point of this new calm in the labor market was roughly in August to November, and since then quits, job openings, and hires have risen. But even at the point of peak-calm, job openings remained historically high, and layoffs and discharges remained historically low.

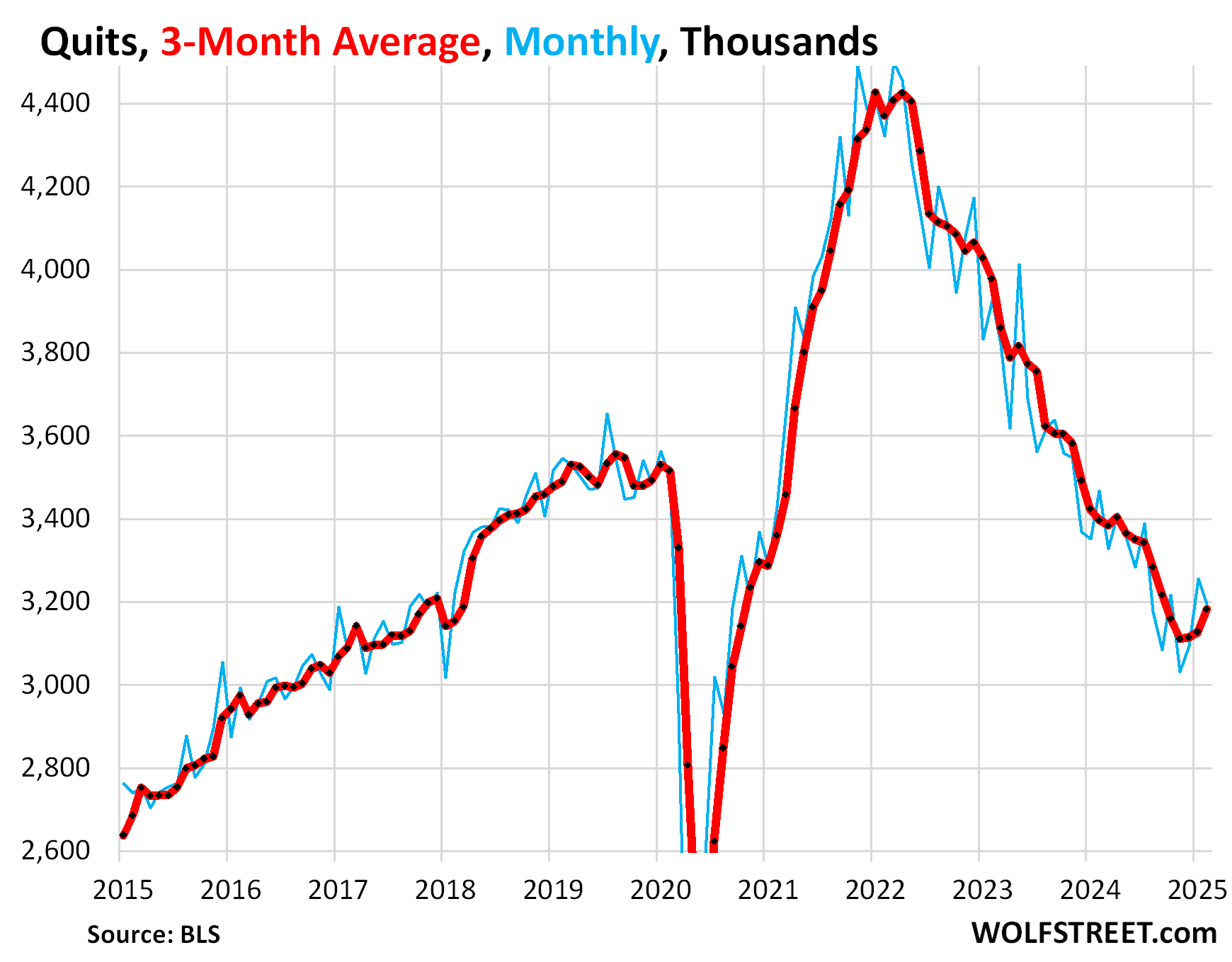

Quits – the number of people who voluntarily quit their jobs – declined by 61,000 in February from January, after a big jump in January, to 3.19 million, seasonally adjusted (blue).

The three-month average, which irons out the month-to-month squiggles and revisions, jumped by 54,000 in February to 3.18 million quits, the highest since September (red).

Quits remain below the levels of the tight job market in 2018 and 2019, attesting to a workforce that is still smarting from having gotten hit over the head with layoff announcements.

In terms of the trend, this is the first multi-month upturn in the three-month average since the peak in April 2022.

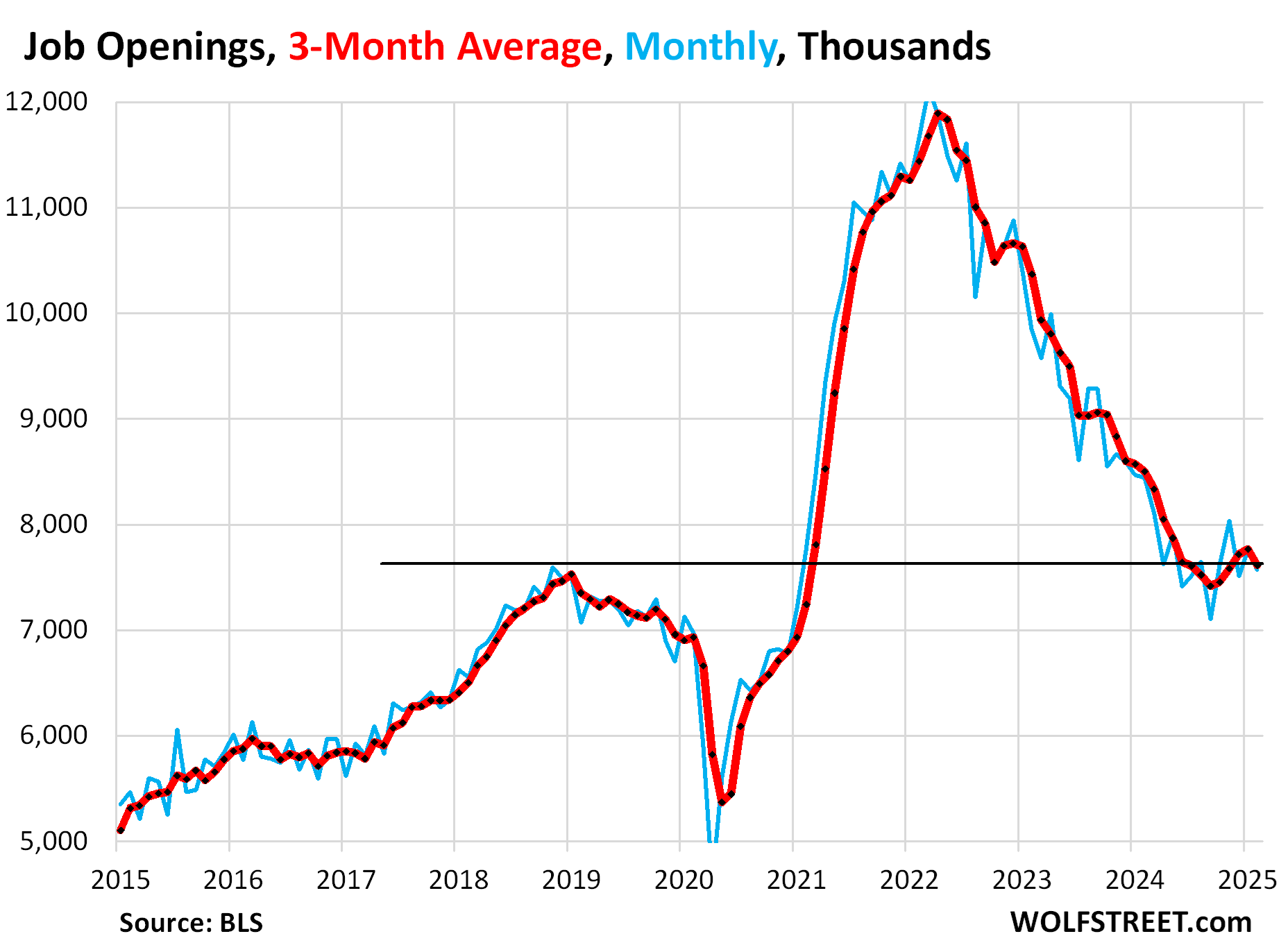

Job openings declined by 195,000 from upwardly revised jump in January (+254,000), seasonally adjusted, to 7.57 million openings. The low point was in September with 7.10 million openings (blue in the chart below).

The 7.57 million job openings are mostly to fill jobs left behind by quits, layoffs & discharges, and other discharges, such as retirements. The separately reported growth in nonfarm payrolls, coming this Friday, reflects the change in total nonfarm payrolls.

This data from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) by the Bureau of Labor Statistics today is based on surveys of about 21,000 work locations, and not on online job postings.

The three-month average job openings dipped in February to 7.61 million, after rising four months in a row from the low point in September (red).

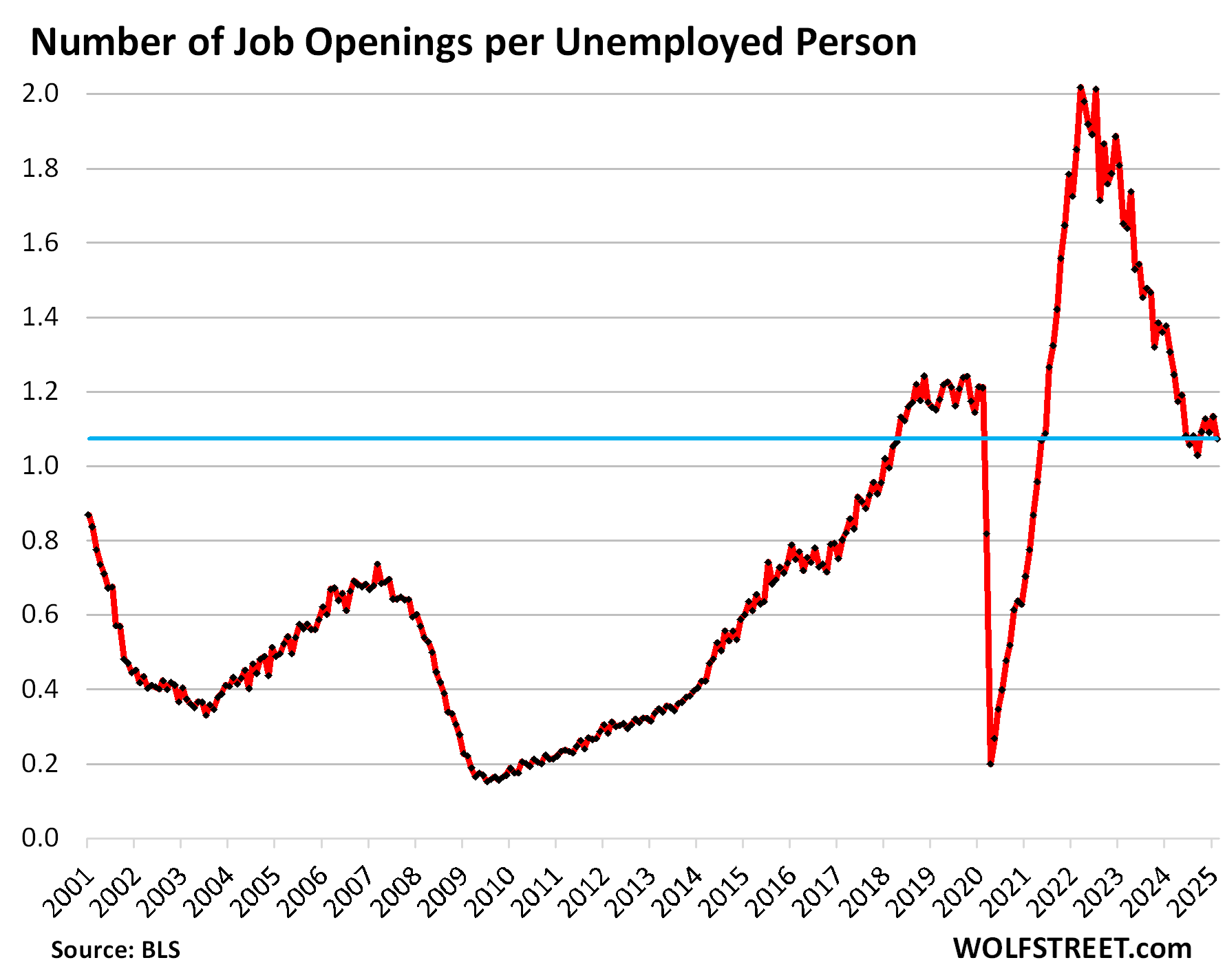

The figure Powell cites a lot: The number of job openings per unemployed person dipped to 1.07 job openings for each person who was unemployed and looking for a job during the reference period (7.57 million openings for 7.05 million unemployed).

The low point was in September, when the Fed got spooked by the direction of the trend, but just then the trend changed.

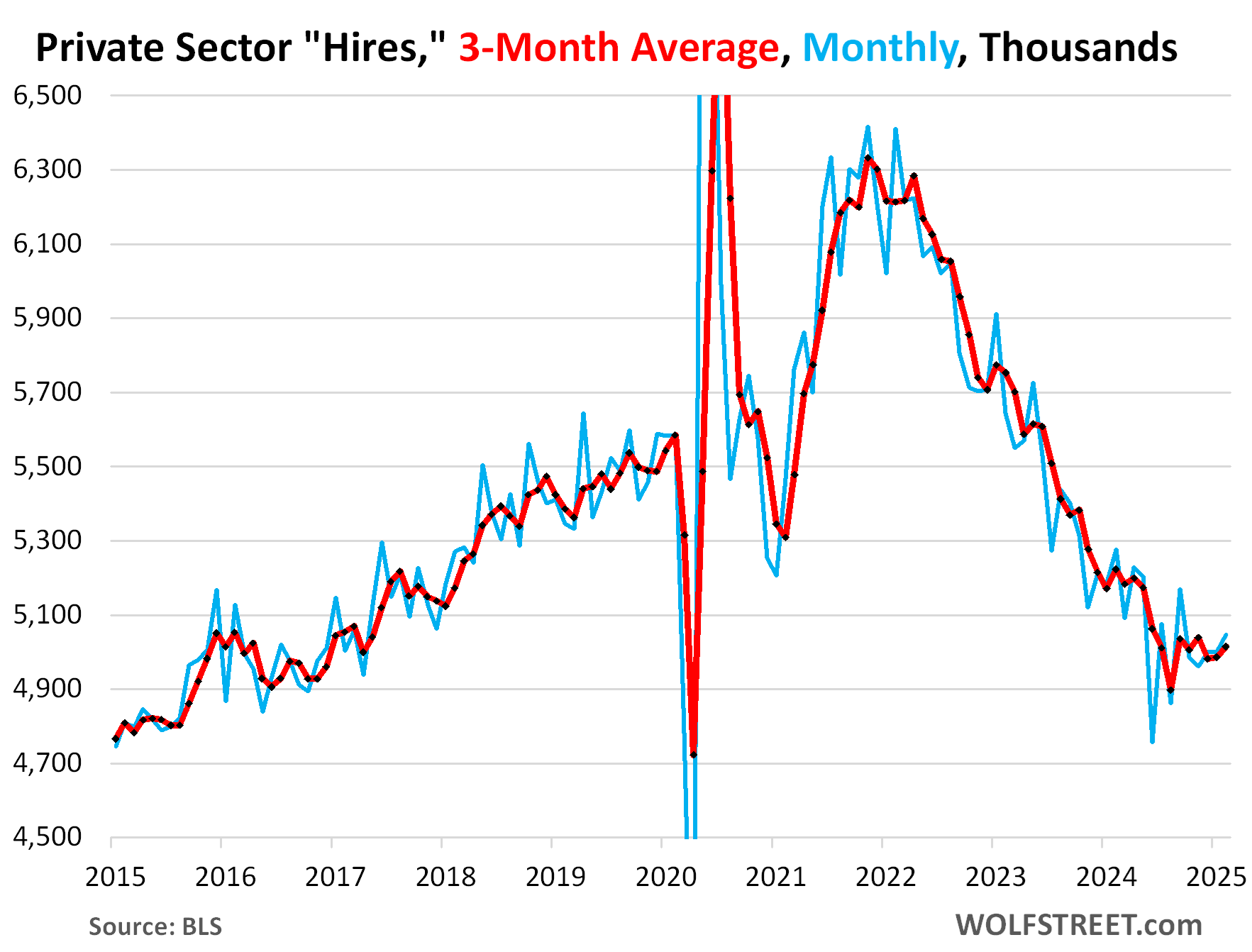

Hires powered by the private sector: Hiring in the private sector rose by 46,000 in February from January to 5.05 million, seasonally adjusted. The low point for private-sector hiring was in June (4.76 million hires).

But government hiring fell by 21,000 to 350,000 hires.

The three-month average private sector hiring rose to 5.02 million. Its low point was in August (4.90 million).

Overall hiring, including government, rose by 25,000 to 5.40 million.

When quits started plunging in 2022, fewer jobs were left behind, job openings plunged, and fewer people needed to be hired to fill left-behind openings, and so hires plunged along with it. But all that has now settled down.

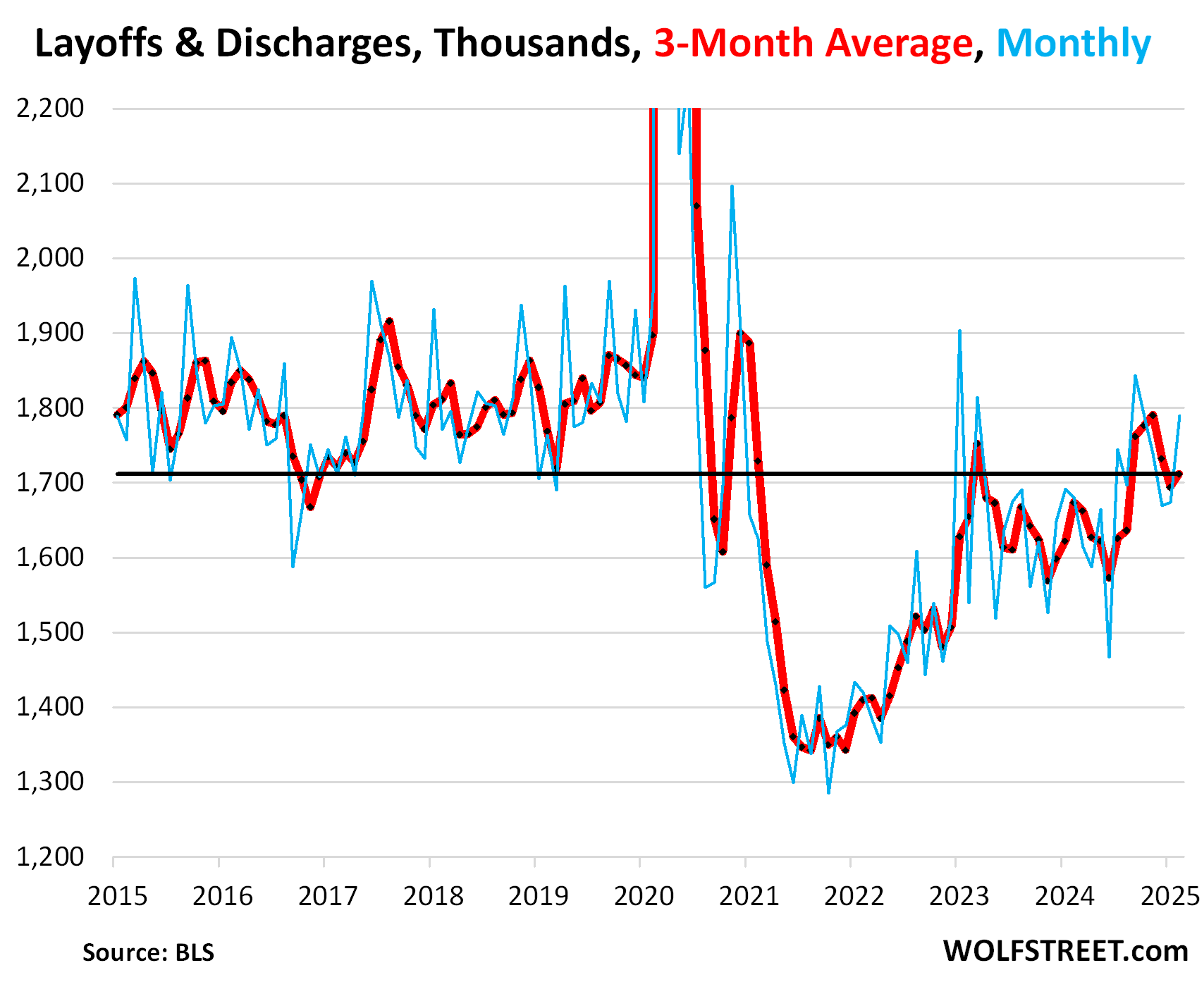

Layoffs and discharges powered by the government: These are workers who got fired with or without cause – a common feature of the US labor market – and workers who got laid off for economic reasons. It does not include retirements, deaths, etc., which are in the category of “other separations.”

Total layoffs and discharges in February rose by 116,000 in February from January, to 1.79 million.

Government layoffs and discharges jumped by 21,000 in February from January, to 99,000, the highest number of layoffs and discharges since the end of the Census-taking period in 2020 that occurs every 10 years.

The three-month average ticked up a hair after two months of big drops.

Despite the surge in government layoffs and discharges, total layoffs and discharges remain at the very low end of the prepandemic labor market.

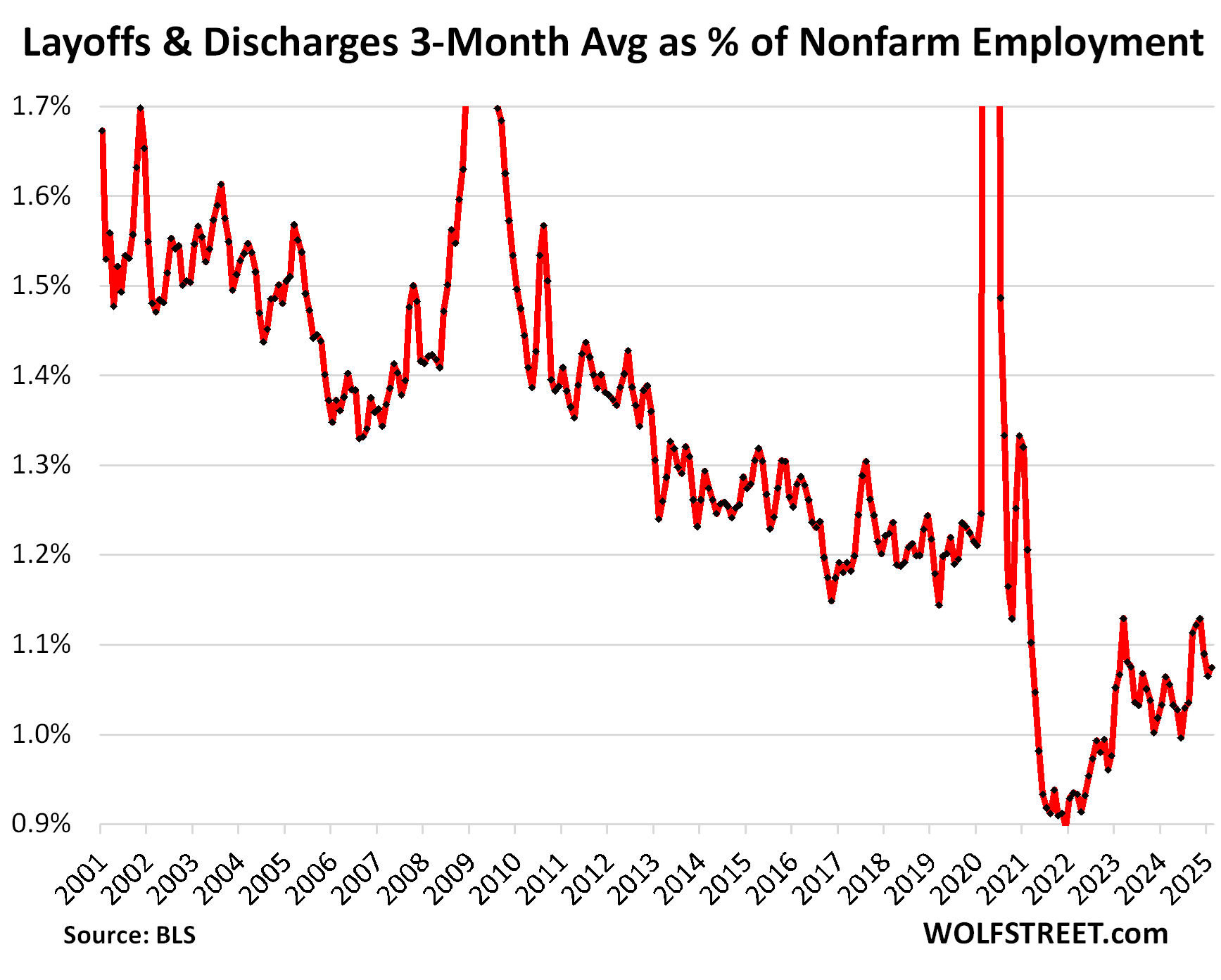

Layoffs and discharges as percent of nonfarm payrolls ticked up to 1.07%, well below any time during the pre-pandemic years in the JOLTS data going back to 2001.

This ratio accounts for growing employment over the years and is the metric that really matters for a long-term view. It shows that layoffs and discharges are historically low compared to the size of nonfarm employment as employers are hanging on to their workers.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

The post Underlying Labor Market Dynamics Still Tight Despite Highest Gov Layoffs & Discharges since Census Wind-Down of 2020 appeared first on Energy News Beat.

“}]]